I’ve always talked to myself. Lately, I find, there’s little I can accomplish, if I don’t talk myself through it. Furthermore, as I find it helps me, I’ve gotten much worse. It seems I talk to myself at all times, about all things, and in the company of others.

I’ve always talked to myself. Lately, I find, there’s little I can accomplish, if I don’t talk myself through it. Furthermore, as I find it helps me, I’ve gotten much worse. It seems I talk to myself at all times, about all things, and in the company of others.

The Name Game

When I go out to work on a machine, one of the first things I ask a user is, “What’s your machine’s name?” You’d be surprised how often I get that funny stare, followed by the reluctant response, and the chuckles I get when I pet their machine and ask it, “what’s wrong?” or “Are you not feeling good today?” I’ve been naming inanimate objects all my life, and I know many others who do. Many of us pride ourselves on finding the perfect name. I actually believe all things already have names, and we just have to pay attention, to figure them out. Sometimes the name is written right on the machine, sometimes it’s related to a quirk or noise, but in reality, does this change how I look at machines as a mechanic? Who can say? I believe to name something shows we see it. It shows that we acknowledge its importance and significance to us, and that we understand it’s something that needs and deserves attention.

Personally, I’ve come to believe adopting your machine as a pet can actually make you a better operator. When you think of your machine as alive, you start to pay attentions to the things that are making it function, you are subconsciously picking up on minor shifts in sound, vibration, or movement that are symptoms of wear, or a change in your machine. When I start cutting, and my machine seems to be having a bad day, its possible I’m picking up on subtle differences in performance that are finally starting to manifest into actual problems, like bearings going bad. This may be similar to when you hear the pitch of a motor drop under load. We are capable of picking up very small pitch changes, and how that pitch changes tells us about how we are stressing our machine, its limits, or how healthy our motor is.

That’s Cheating

Ever have someone walk by while you’re cutting and say, “That’s cheating!” I have. When we do conventional cabinetry or carpentry, the connection between our creativity and our creation feels like it is just our hands. But when we CNC, we start to see the steps between this process. As operators we’ve come to understand we exist, more and more, in the world between the machine and the software, and do less with our own hands. This is balanced differently by everyone. These steps we go through to create something, are our process, and everyone’s process is different.

Process

More and more, I have come to view all innovation in digital fabrication as unique advancements in process, more than advancements in technology. I am guilty of using the term frequently as the foundation of all hypothesis, so be prepared to hear the term in every blog! I would propose, how each operator develops and nurtures these steps of process, is what makes them truly innovative or brilliant. The idea of the machine doing the work for us, or “Cheating” is irrelevant because that is not where the true craft is happening anymore.

The Rise of The Machine

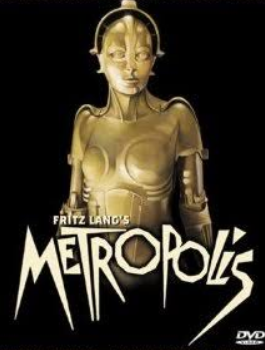

Dehumanization has been a common idea in culture as long as there has been society. We see it everywhere, in literature, in music, in art, and movies. Humans have always felt replaced by changes in society, let alone advancements in technology. There are countless examples of this throughout history, and researching it on line was overwhelming. The earliest references I found, were Aristotle’s essay to Fry on slavery, where the idea of dehumanizing people by changing them into animals, was referenced in tales of the gods.

But you don’t have to look far to see this theme everywhere. The Industrial Revolution, Fritz Lange’s 1927 film, “Metropolis”, the movie, “Tron” even Pink Floyd’s “Welcome to the Machine” or Charlie Chaplin’s, “Modern Times” are just a few examples of the classic theme of people feeling displaced by technology.

In an article from 1976 by Phillip Sherrard, Phillip had some excellent insight.

Quote; “In this world-the world of artificial environment, the sophisticated manipulation of machines and techniques-the human element is gradually being eliminated.”

And later in the same article; “There is, however, a price to be paid for fabricating around us a society which is as artificial and as mechanized as our own, and this is that we can exist in it only on condition that we adapt ourselves to it.” The subject is vast, and mostly expresses the same concepts.

I’ve always had a crush on this robot.

I’ve always had a crush on this robot.

A Friend in AI

The idea to anthropomorphize the inanimate things with which we are closes, is normal. Look how, as a culture we have embraced a concept like Siri on our phones. I talk to her, like I talk to my best friend. Frankly, she’s more helpful than a lot of my friends, and doesn’t ask me for money. As a culture, not only are we accepting of machine-human interaction, we embrace it.

While dehumanization has always troubled us, one defense mechanism we’ve developed is that no matter how overwhelmed we become, we translate our activities back into human state, or we redefine our experience into human terms. In my case, with CNC, I find myself stroking it, touching it, absorbing and listening to its vibrations. I become attuned and immersed in its sound, touch and smell. For me, CNC has evolved into an interaction between two close friends, and this ultimately affects my process, my development of the steps I use to create, and the limitations of what I can accomplish.

Embracing Your Inner Mechanic

We can’t always explain why we know something is wrong with our machines when it happens. We typically catch ourselves feeling like something isn’t right, but we don’t have a reason why. Sometimes it is overt, or sometimes, perhaps, we subconsciously hear, smell, or see something that has triggered an alarm and we don’t even realize it. Does this make us better operators, I believe it does. Not only does it help us balance the unspoken psychology of human and machine, it makes us see our machines differently. It translates our mechanical understanding into terms we understand.

The realm of digital fabrication has proven to be far more creative than most of us have ever expected. And the reality of physically making something is, perhaps, more layered and complex than I believe most of us give it credit for. If you’re like me you just make stuff without ever thinking about this, but the mechanical aspect of understanding and maintaining our machines, and our relationship to them, is an inherent step in our process as I have defined it above. I would encourage operators to understand that quirkiness towards our machines is not only harmless, but can help you be a better operator. It can cause you to embrace your inner intuitive mechanic, and help enrich your process.

All images used in this article have been altered from their original form.

All images used in this article have been altered from their original form.